Corbynism or barbarism, part II

I’m going to be voting for Labour.

This is a new experience for me. It’s not that I haven’t voted Labour before: I did in 2010. Posturing and frightened in a low, scuzzy student block in Leeds, I pulled myself out my personal bathysphere of weed stink and late-teenage ripeness to plod over under crows and clouds and do my duty and keep out the Tories – and afterwards I felt deeply ashamed. It was like having one of Gordon Brown’s hairs stuck in my mouth; it was as if his grease had started oozing through my skin. I felt suddenly complicit in everything – the wars, the privatisations, the ASBOs and ID cards, the scudding lies and shabby gloss of New Labour Britain. Five years of Tory government acid couldn’t burn off the guilt. I promised myself that I wouldn’t ever do it again, and when I had the chance two years ago, I didn’t.

I couldn’t bring myself to do it. It’s not that they were just as bad as the Tories; the government had been a half-decade horror. a cast of seepy flesh-bubbles bloating out the mire, some murderous gang of ninnying imbeciles and swill-fed ponces that had, for all the usual reasons, decided theirs was the right to go about making life quantifiably, measurably worse. I hated them and I wanted them gone. But I couldn’t vote for Labour. I couldn’t stand hearing Ed Miliband’s voice on the radio, because it was the honk and bleat of someone who was basically just like me, another nice left-wing Jewish boy from North London, a bit clumsy, a bit gangly, a bit insecure – but one who didn’t indulge in my purism, or my nihilism, or whatever it was that made me refuse compromises and triangulation and any attempt to make common ground with established power. Any student of history knows what power does to the commons. I would not settle for the least worst option; I would not pick sides in the stupid intra-capitalist squabbles of electoralism. I knew that a Labour government would materially reduce the suffering and deprivation of millions of people – but I also knew that once you let that turn into an ethical duty to vote, anything beyond the minute reduction of suffering is lost, and worst of all, the suffering of others (migrants, asylum seekers, the global working class) becomes something utterly hideous: a worthwhile price. When I voted for some tiny Menshevik party I didn’t really like and whose name I can’t even remember, it didn’t help anybody. But who says our capacity to help, to do politics, to be engaged, has to be bounded by the form of the vote?

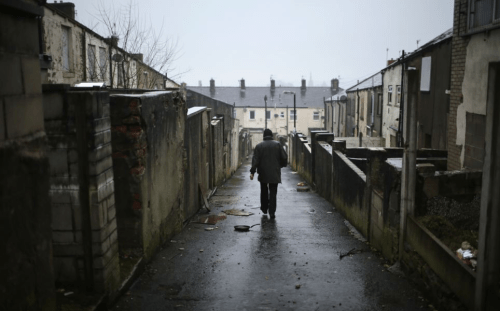

Since then things have become immeasurably worse, but that’s not why I’m voting for Labour. Britain is not just sliding into fascism; we’ve landed. This has become a deeply ugly place. Our Prime Minister – gurning, grimacing, parochial, incompetent, rhadmanthine, segmented, arachnid, and inhuman; the Daily Mail letters page given chitinous flesh; a zealous ideologue for the doctrines of smallness and stupidity and dumbfuck blithering hatred; a vicar’s daughter distilling all the common-sense peevishness and resentment from the dingy grog of the English national spirit; a leader who doesn’t so much impose austerity as embody it, in every word or gesture that seeks to foreclose on all possibilities and draw the furthest boundaries of the sunlit world no further than your respectable lace curtains – instructs the public to give her more power, to paint over a divided country with a false unity in Parliament, so she can exercise her supreme will. The loyal Tory press responds with terrifying outbursts against all enemies: ‘Hang The Lot,’ ‘Boil The Traitors Alive,’ ‘Insert The Pear Of Anguish Into The Anuses Of Our Enemies So That They May Be Disembowelled From Within,’ ‘Readers Agree: It’s Time To Crush The Heads Of The Remoaners Under A Large Millstone,’ ‘Where Are Our Common-Sense Torture Kennels In Which The People We Don’t Like Are Torn Apart Shred By Shred By Starving Dogs?’ All the anti-establishment energies that fuelled the Brexit vote have been effortlessly consumed by the administration: the people had their say, and (given that this is all out of the Schmittian playbook) they will only get to have it once; now it’s the role of power to implement it, and the will of the people as refracted through this government is for total centralised power with anything that could be called political extinguished. This is fascism: a simple, easy, descriptive term for what it is we’re living under.

But I’m not voting against Theresa May. I’m voting for Jeremy Corbyn.

It’s easy, very easy, to be against something. I was against Labour in 2015, and I still don’t think I was wrong. But being purely against – anti-fascist, anti-liberal, anti-racist, anti-sexist – means never being let down, and never being vulnerable. The horrors of the world descend on you, and you oppose them. But it’s not enough. There needs to be some positively articulated shared object, something that can be affirmed. It means losing some cynicism, giving up some of the invulnerability of ironism, attaching the boundless subjective I to a thing of history, that could get swept up with every other fragile thing and destroyed. But without that attachment nothing can be done. This is why so many socialists still see a value and an importance in maintaining some kind of attachment to the old dead Soviet project – people who know full well that there were famines and purges, mass deportations and mass shootings, and who are repulsed by all suffering, but who know that, whatever its failings, the Soviet project was our project. Socialism is not an abstraction or a negation; it’s the real attempt to build a better world in this one, and it demands our fidelity. It won’t be possible unless we’re prepared to do more than oppose the evil. Demands are made on us for the sake of a liberated existence, and the first is that we be prepared to make ourselves vulnerable, and that we accept that our faith might be disappointed.

To be for Jeremy Corbyn is dangerous, and the possibility of disappointment is high. His ideology is not the same as mine; his policies, while good, are disarticulated; his leadership, while inspiring, has not been effective; most of all, the Labour Party might be the worst vehicle possible for a programme of genuinely egalitarian change. It doesn’t matter. If he loses, the suds and mediocrities of the party’s right wing will be relentless; if they manage to force back the leadership, they will go to work destroying absolutely anyone who still holds the belief that life can be made better, burying the idea in its fringes for another generation or more, rooting out the seeds of utopia wherever they’re planted. The Labour party will be refashioned into something that once again proposes Tory policies using Tory methods and with priorities, just as the Tories skid further into authoritarianism – but while the Tories will just flatly tell us that they do evil because that’s how things are, Labour will still be begging to have a go on the torture kit so they can make things better. And people might believe them. After all, it won’t be quite as bad as the alternative.

Corbyn stands for a refusal to accept something that’s just not quite as bad as the alternative. Corbynism means not just electing the least fascist, the least liberal, the least racist, and the least sexist. The Labour right, the Tories, the Lib Dems, and Ukip are all partisans of a restricted imagination and a penny-pinching common sense; Corbynism the possibility of something actually good, the possibility of a way out. It points beyond itself. Jeremy Corbyn did something quietly incredible, and which has nothing to do with his actual performance as Labour leader: he acted as the signifier that brought together a collectivity, he formed a point of unity for everyone who wanted a radical and transformative social change, even if they didn’t agree on what it should look like or how to bring it about. He gave the left a space to assert itself openly in British politics, in surprising numbers. This – the collective, not the man – is what’s important, and what’s feared, and what our enemies are desperate to crush.

After all, it wasn’t meant to be like this. There is a programme now for Western politics: it’s what we saw last year in the United States, and what’s unfolding right now in France. Wets versus Nazis, the collapsing liberal order against the embodiment of its own internal collapse, reiterated over and over again in every country, politics as a looping gif, the juddering replay at the end of the world. No hope, no possibility, this or the abyss. The radical left still has a role to play: its role is to lose. You thought you could have something better, and it turns out that you can’t: now choose. Centrists are obsessed by the idea that radicals secretly prefer the fascists to themselves; as soon as the hope for anything better is extinguished they demand that everyone on the left loudly announce how much they prefer the status quo to the remaining alternative. We have to pick sides in what is essentially a family squabble among reactionaries. Isn’t Hillary Clinton better than Donald Trump? Isn’t Mark Rutte better than Geert Wilders? Isn’t Emmanuel Macron better than Marine Le Pen?

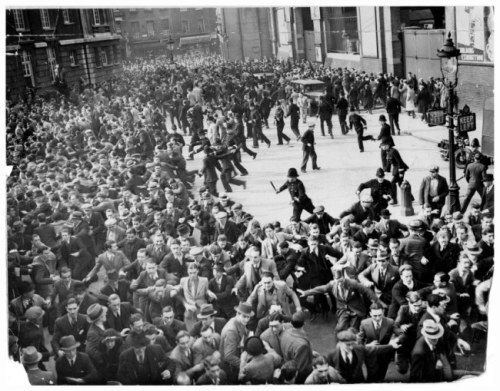

Yes, of course they are. However badly things are going, they could always get worse. But the final collapse of liberalism is a situation in which liberalism seems perversely comfortable. Anti-fascism is only one half of what the world needs; it also needs a positively articulated vision of how it can be improved, and the centrists have nothing: lower business rates, softer racism, friendlier faces. Of course it’s necessary – urgently, frantically necessary – to defeat the Nazis, not least because it buys us more time. But it’s not enough, it’s a stopgap for the symptoms. Almost all the advanced capitalist societies are tilting in the same direction, and these Nazis didn’t come from nowhere. They are entirely immanent to the liberal political order as it stands; their racism and violence and hatred comes from a society which is already racist and hateful and violent. The fascists gain their energy from the failure of liberalism, and liberalism gets to stave off its failure thanks to the threat posed by the fascists. Both are the living undeath of the other. The whole order is monstrous, decrepit, shambling, and lifeless; it has to go. To struggle for a better world isn’t a luxury in a time of rising fascism, it’s the only thing that can save us.

I’m voting for Labour. It’s not perfect, of course it’s not. And Labour are unlikely to win. Corbynism or barbarism doesn’t represent a fork in the road, but something much harder; barbarism surrounds us everywhere, and Corbynism is attempting to wrench us out of it; it’s hard to pull an entire planet out of the swamp it’s made for itself, it’s hard to lift something up when it’s already slipping down, it’s hard to tear yourself away from a brutal and stupid reality. But it can be done. Something like Corbynism was never meant to happen. The narrative failed here: where there should have been a brief entrancing spark of hope followed by another grim round of which-is-worse centrism-or-fascism, that spark refused to be snuffed out. It’s burning lower than I’d like, but it’s still there, and while it is, I’m voting for Labour.

Corbynism or barbarism, part I, written during the last Labour leadership election, is here.