The Englishman and the Octopus

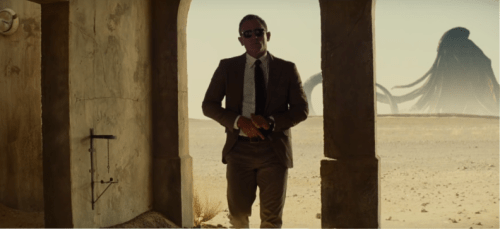

If you’ve seen Spectre, it should already be obvious to you that the James Bond franchise is a spinoff, taking place entirely within HP Lovecraft’s Cthulhu mythos.

Say 007 arrives at Mexico City Airport at four in the afternoon. He goes through customs. He takes a taxi to his blankly intercontinental chain hotel. He makes himself a slapdash vodka martini from the little bottles in the minibar, pouring the entire stub of vodka and a passionless vermouth glug into one of the film-wrapped plastic cups from the bathroom, and drinks it on his balcony. He looks out at Mexico City, and something looks back. The Cthulhu mythos only works if its characters don’t realise that they’re in it. When done right, Cthulhu stories don’t need to actually portray the Great Old Ones; they can lurk in the deconstructive background, appearing as a hollowness in the mise-en-scène, a spacing and a vastness suspended just beyond sight. Another recent film about Anglo imperialists in Latin America, this year’s Sicario, was an example of what could be called ‘landscape horror’, fine-tuned to Yanqui racism: long panning shots of barren or broken landscapes, the blasphemous edge between lawnmower-perfect American suburbia and the desert beyond, or Mexican cities that seem to sprawl without reason over the hills and valleys, protoplasmic shoggoth-blots poised to gobble up the border. This isn’t the ordinary Burkean sublime, but something far stranger. Ciudad Juárez is ‘the Beast’; the scarred and hollowed-out Earth is itself a cosmic evil. Bond on his balcony faces a city that does not end, from horizon to horizon. Where are the goons? Usually this is when some gormless lunks try to jump him, and from there it’s only a short kidnapping to the supervillain’s lair, where someone will tell him everything he needs to know, saving him the trouble of doing any detective work. Instead, there’s CNN, complimentary soap, and blithe miles of homes and highways. It’s hard not to feel lonely. It’s hard not to feel afraid. He’s in Lovecraft territory; those trillion-tentacled monsters from outer space that intrude upon stately New Englanders were always a barely concealed metaphor for one man’s horror of black and brown bodies in their nameless shoals, leaking degradation over a world fissuring from imperial decline. But over and above that, they stand for a universe that is not required to make sense.

James Bond, meanwhile, is a man in search of the transcendental signifier. It’s hard to do a Bond story these days, with the end of the Cold War, the rise of feminism, and an inherent ridiculousness to the form that perfectly crystallises itself in Austin Powers, which managed to carry out a satire of the Bond films simply by replicating them in every detail. But before there could be Austin Powers, there was Thomas Pynchon. His novels (especially V, with its deliberate Bond insert) subject the spy story to the (un)logic of post-structuralism. In spy stories the hero jets off around the world in search of the Thing that allows disparate events to reveal themselves as products of a singular Plan. In Pynchon, this structure is preserved, but knowing as he does that the object petit a does not exist, he simply takes away the MacGuffin. Bond’s shark-sprint for the truth falls apart into a messy and ever-widening entropic spiral. Postmodernism posed a far more serious threat to MI6 than Soviet spies ever could. Bond’s response was sloppy. At the start of the Daniel Craig era, the franchise put away most of Pierce Brosnan’s silliness for a lot of dark and gritty po-faced nonsense; the resulting films were basically terrible. In Skyfall, it reacted with a kind of watered-down postmodernism of its own, a plot barely held together by its spider’s-web network of smug self-references. Spectre – by far the best Bond film in recent decades – was at this point probably inevitable. Orbis non sufficit: the world is not enough. The villain in Casino Royale was only a puppet of the villain in Quantum of Solace, who was only a puppet of the villain in Skyfall, who was only a puppet of the villain in Spectre: you can only take this kind of thing so far before the evil grows beyond one lonely planet’s capacity, and plunges into outer space. With his metanarrative collapsing around him, James Bond escaped into a new one, a lair where Pynchon or Powers couldn’t find him. He escaped into HP Lovecraft.

This film doesn’t exactly hide its place within Lovecraftian mythology. You really think that creature on the ring is just an octopus? Uniquely for a Bond film, it starts with an epigraph of sorts, the words ‘the dead are alive’ printed over a black screen – a not particularly subtle allusion to the famous lines from the Necronomicon: ‘That is not dead which can eternal lie/ And with strange aeons even death may die.’ In the credits sequence, vast tentacles coil around him as he murders and fucks his way to an absent truth. In his house at R’lyeh, dead Cthulhu waits dreaming. The villain’s base is built around an asteroid, glossy and scarred, that fell from the sky millions of years ago. You almost expect alien ooze to start trickling from its cavities. With 1979’s Moonraker, heroes and villains invaded outer space; in Spectre it’s the other way round. And in its Lovecraftian context, everything starts to make a lot more sense. Why do Bond villains always explain their entire plan to 007 before killing him? Real-life conspiracies (like the financial markets, the internet, or history in general) are not so much secret as unspoken; they fold themselves into the basic fabric of social life, so that it’s often impossible for anyone at all to stand outside their situatedness and articulate what’s going on. Lovecraft’s monsters, on the other hand, live in the permanent outside; they don’t need to worry about revealing themselves to you, because they know that as soon as you clap eyes on even the shadow of their true form you’ll go irretrievably mad. For Cthulhu to reveal himself is not weakness but power.

Spectre is a film that deliberately resists any sense for the climactic or any libidinal payoff; all we get is lingering dread. The first post-credits chase scene is downright weird; Bond and his adversary race sports cars through the centre of Rome, but the gap between them never closes, the backwards-firing machine-guns don’t have any ammunition, and the sequence just keeps on going, all thrill long dissipated, until it takes on a kind of shambling undeath. ‘The longer the note, the more dread.’ Brecht calls this Verfremdungseffekt: by refusing to simply give pleasure to an audience, you prevent them from ever being entirely immersed in narrative events; they begin to consciously interrogate the fragility of the social conditions that hold up any action. But overall the Italy sequence is short. Bond’s never really been at home in Catholic Europe; he’s a creature of the Western hemisphere, and in particular the Caribbean. Gorgeous, tiny islands with their histories bayoneted out of existence, places where the hotels are luxurious and the bar staff eager to please. So Spectre gives us Moroccan scrubland instead, flat and impoverished, neither beautiful nor sublime, just two thin tracks plunging through a plane without interest forever. When there is an invocation of orgasm, it directly undercuts any myth of the secret agent’s sexual prowess. In the third act, we get an ironic version of the usual Bond structure: he’s taken to Blofeld’s secret lair (white cat and all), invited for drinks at four, and told the whole plan. So far, so good. Then, after nearly being killed in a pointlessly baroque way, he escapes, fires six shots, and the whole base explodes. Is that it? There was a big bang, sure but it was all over too soon. If you ever wanted to know what it’s really like to have sex with James Bond, Spectre is here to tell you.

But of course that’s not it. After orgasm, nightmares. The traditional ending is followed by a strange and shadowy coda in London: Bond, collapsing into a ruined MI6 building, finds his name and an arrow spraypainted on a memorial to the dead. He follows it. Shades of Lot 49: for the entire film, he’s only acted on the instruction of the omniscient dead. Older Bond outings allowed us to notice the essential powerlessness of the hero in a world always determined by its villainous Big Other, and feel very smart for having picked up on it; here, it’s thrown mercilessly in our faces. A mural at the mountains of madness. Spectre constantly frustrates the pleasure principle; it’s an awed testament to a Todestrieb that, itself unrepresentable, appears only in the spacing and repetition of something else. James Bond is no longer a brutal, neurotic male wish-fulfillment fantasy: he has no will of his own, no love for his own life, and he can’t even fuck. He falls into the grasp of something else, vast and pitiless, the key and the guardian of the gate, that watches the tiny escapades of Her Majesty’s Secret Service from far beyond the stars.